An unprecedented wave of chronic absence has spread across the country. New data from the U.S. Department of Education show striking findings at the school level: In 2021-22, two-thirds (66%) of enrolled students attended a school with high or extreme levels of chronic absence. This means at least one of five students in their school was missing almost four weeks throughout the school year.

These exceptionally high levels of chronic absence are an enormous increase from levels before the Covid-19 pandemic, when only a quarter (25%) of all enrolled students attended schools with high or extreme chronic absence. Not only is teaching and learning more challenging when large numbers of students are frequently missing class, such elevated levels of chronic absence can easily overwhelm a school’s capacity to respond.

Turning the tide requires all of us to work together – at state, district, school and community levels – to avoid blame and instead partner with students and families to address the issues that keep them from showing up every day. Fortunately, numerous evidence-based interventions are available that can be tailored at the local level.

Released through Ed Data Express, the national data show that chronic absence nearly doubled, rising from 16% before the pandemic to nearly 30% by 2021-22 school year. This means that nearly 14.7 million students (29.7%) were chronically absent in the 2021-22 school year. The jump in absences shows that roughly 6.5 million more students were missing 10% or more of school days, when compared with the school year prior to the pandemic.

As this table shows, how much chronic absence rose varies by state. These findings are similar but slightly different from estimates offered earlier in August based upon data released by 40 states by Professor Thomas Dee of Stanford University.

And while many had anticipated that daily attendance would return to levels seen before Covid-19 closed schools, early data from the 2022-23 school year reveals that absenteeism has remained extremely high. Read more about 2022-23 data in this short blog post.

A close look at 2021-22

Clearly the return to in-person schooling was far from easy. In the 2021-22 school year, significant outbreaks of Covid-19 occurred throughout fall and winter. Students were missing extended numbers of school days due to being quarantined. Some schools returned to virtual instruction for some students – or all students – for periods of time.

Many students struggled with untreated health needs and unstable transportation as well as increased family and work responsibilities, especially those in high school. Too many students experienced trauma, with over 1 million losing a grandparent and over 200,000 families losing a primary caregiver. After months of isolation, re-establishing positive school climates and helping students develop the skills to resolve conflicts was not easy. Staffing shortages made building relationships with students and families and ensuring engaging curriculum especially difficult. Anxiety grew as students struggled to keep up with learning as well as forge connections to peers after extended periods of absence. In addition, myths about the unimportance of missing school may have been heightened by parents’ and students’ experiences with virtual schooling during the pandemic. All of the root causes of chronic absences worsened during this time.

National research shows these extremely troubling increases in chronic absence are associated with significant declines in student achievement and threaten efforts to recover from the pandemic.

Overcoming this attendance crisis is not a short- term endeavor. Rather, ensuring all students have an equal opportunity to learn in the aftermath of the pandemic will require strategic and long-term investments aimed at reconnecting and re-engaging students and families in school. Reconnecting with both students and families is critical for putting in place meaningful solutions to support academic success and re-establishing a norm of attendance every day across the nation.

Stunning increases in schools

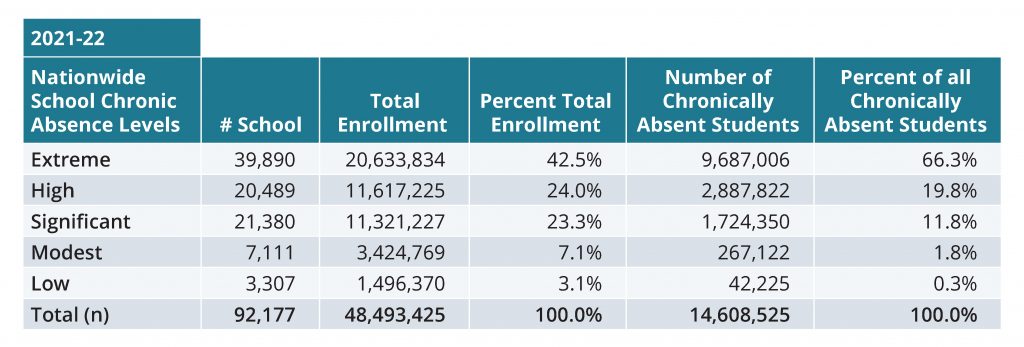

The new data yields additional critical insights at the school level that can inform the development of solutions. The most striking finding is the extraordinary shift in the extent to which schools, as a whole, are affected by chronic absence. In 2021-22, two-thirds of enrolled students, (32.25 million), attended a school with high levels (20-29% of students were chronically absent) or extreme levels (30% or more were chronically absent.)

This is an enormous increase from the 2017-18 school year when only a quarter (25%) of all enrolled students attended schools with high or extreme chronic absence. As a result, the chronic absence wave has spread, and many more students and schools are, for the first time, experiencing high and extreme levels of chronic absence. (Please note that an analysis of the 2018-19 school year is not provided because school level data was not available for that year.)

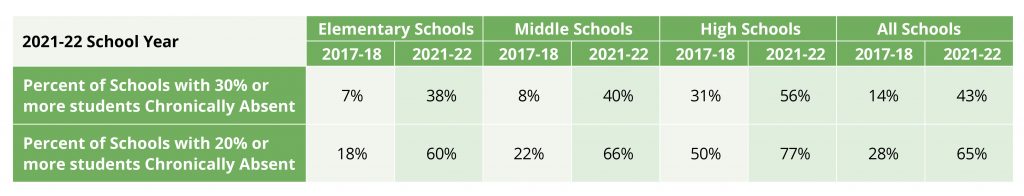

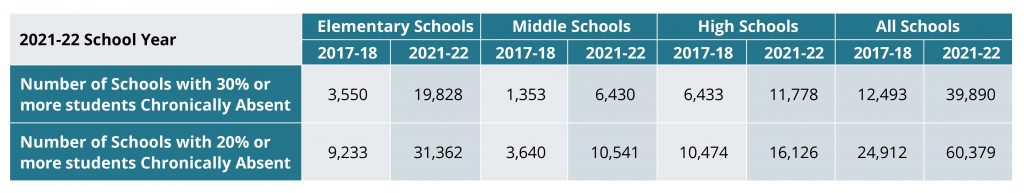

By 2021-22, 43% percent of schools had extreme levels of chronic absence. Elementary schools were especially affected with extreme chronic absence jumping from 7% to 38% of all elementary schools. See table below.

By 2021-22, the number of elementary schools with extreme levels of chronic absence far exceeded high schools (19,828 vs. 11,778). See table below.

Most of this increase occurred in regular education schools (vs. schools focused on special education, vocational education or alternative education) which experienced a four-fold increase in the number of schools with extreme chronic absence, from 10% to 41%. See attached spreadsheet.

Such a rapid increase in the level of chronic absence easily overwhelms a school’s capacity to respond. Increased chronic absence rates in 2021-22 meant that an elementary school with typical enrollment and a chronic absence rate equal to the national average for elementary schools had about 100 chronically absent students, a similar middle school about 150, and a similar high school about 200. Such high numbers of chronically absent students are beyond the capacity of a single social worker or counselor to address.

Unaccustomed to such significant numbers, many schools may not have had in place an effective tiered approach to improving attendance. As a result, not only were more students chronically absent, but fewer chronically absent students may have received the support and responses that would reduce chronic absence, especially given that Covid-19 was causing illness among teachers and the pandemic deepened already existing teacher shortages.

The sheer magnitude of the number of chronically absent students could also create the incorrect impression that missing a few days of school is not a problem, resulting in a relaxed attitude towards getting kids to school everyday.

How can we respond?

Turning back this wave of chronic absence must be a national, state, district, school, and community priority because it affects the success of most, if not all, efforts to help students recover and thrive in the aftermath of the pandemic. These high levels of chronic absence demonstrate the urgent need for systemic responses that rebuild a culture of daily attendance by investing in the underlying positive conditions for learning in schools that motivate showing up while also removing barriers to attendance. This means we must redouble actions to create physically and emotionally healthy and safe learning environments while also cultivating a sense of belonging, connection and support for every student and family. We must offer relevant and engaging learning experiences as well as provide flexible and meaningful opportunities for students who missed out on extended periods of school to learn, gain credits and graduate. We must invest in staff health and well-being, address staffing shortages, and leverage the “people power” of community partners as well as youth themselves to ensure the bandwidth exists to support our students and families despite challenging conditions.

We don’t have to start from scratch, rather we can build upon what has been learned about effective responses to chronic absence over the past decade or more. See for example, the Attendance Playbook and Learnings from the Grad Partnership with interventions that work.

We must advance programmatic and policy solutions, including for example, community schools, that help districts and schools address the challenges that make it hard for students and families to get to class and affect their ability to learn even when they do show up. These include, for example, the lack of health insurance and health care, unreliable transportation, unsafe paths to school, food insecurity and unstable housing. We can also establish community-wide campaigns that re-establish daily attendance in school as a top priority and convey to everyone why it matters for student well-being and success. The size and scale of the challenge merits and requires an all hands-on-deck approach.

To be effective, these systemic approaches must also recognize the strengths families, students and communities bring to the table, as well as their day-to-day realities. Doing so requires we avoid counterproductive punitive approaches that alienate students and families.

This analysis is the first of a three-part series unpacking federal chronic absence data. Read part two, All Hands on Deck: Today’s Chronic Absence Requires A Comprehensive District Response and Strategy, and part three Turning Back the Tide: The Critical Role of States In Reducing Chronic Absence.

By Hedy Chang, Executive Director, Attendance Works; Robert Balfanz, Director, Everyone Graduates Center, Johns Hopkins University; and Vaughan Byrnes, Senior Research Associate, Everyone Graduates Center, Johns Hopkins University.