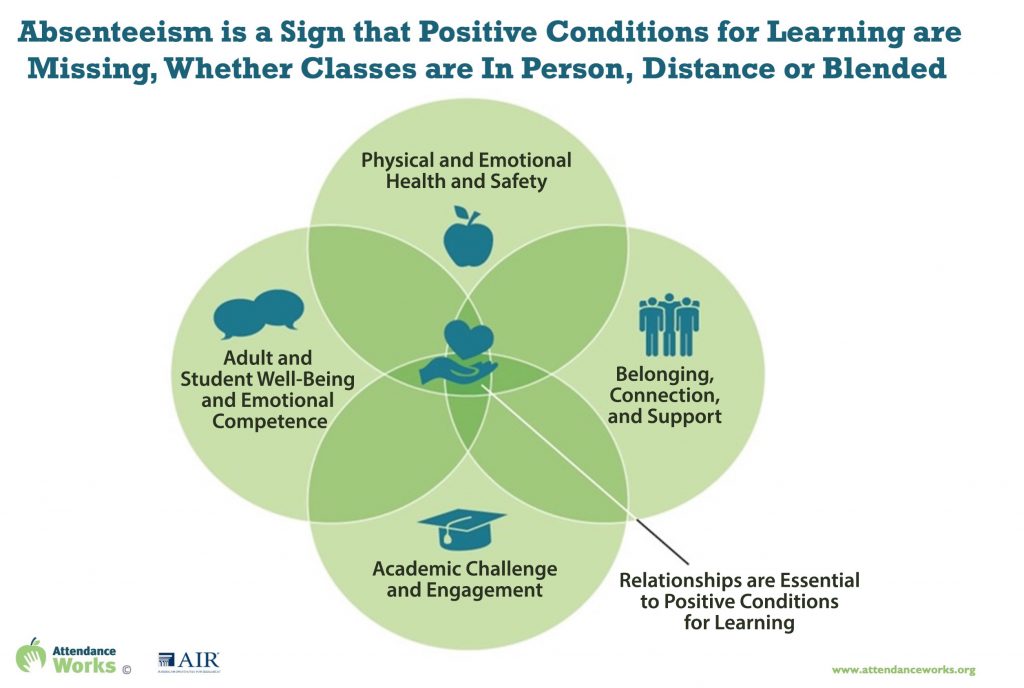

When positive conditions for learning are in place students are more motivated to attend and engage in learning. In collaboration with AIR, Attendance Works developed a graphic (see figure) showing how chronic absence is a sign that positive conditions of learning are missing. Attendance Works Executive Director Hedy Chang talked with David Osher, Vice President and Institute Fellow at AIR, about why this framework matters even more now and why it now includes the concept of well-being.

Hedy: Our report, Using Chronic Absence Data to Improve Conditions for Learning, explains the four conditions that can impact attendance: physical and emotional health and safety; belonging, connectedness and support; academic challenge and engagement; and adult and student social and emotional competence and how relationship lie at the center. When we first developed this framework why did you think it was so important ?

David: We live in a country where we tend to think that people own their problems and are the solutions to their problems. Although every individual is a key part of changing things, they always do what they do in conditions that involve other people. When we look at issues of attendance, chronic absence and truancy, we have tended to only individualize them and see the child and the child’s family as the problem, when in reality what happens when a student goes to school or doesn’t go to school, is engaged in learning while at school or not engaged in learning while at school, is produced by what is happening with them. Are they in good health, are they motivated and can they motivate themselves? These outcomes are also powerfully influenced by what schools do and what communities do to enable students to be in school, to encourage them to want to be in school, or to push them out. The process of somebody not attending and not coming back to school or dropping out later on is not solely in the individual, it is also because of the experiences that she or he has in school.

Hedy: We have found that when we show educators the graphic, it resonates with them because they see the role they can play in affecting whether or not a student shows up to school or engages in learning at school.

David: When I think about students who don’t continue in school, there are many factors [that come into play such as] cultural, economic and transportation factors. What also happens is that when students go to places that are not engaging, that are not affirmative, where they just feel that they are failing or that people don’t respect them, they do not want to be there. What schools need to do is both support people being there and also make them want to be there, and not ignore the factors that may make it hard for students to attend school.

Hedy: We are in unprecedented times, with a pandemic that is doubling and sometimes tripling the levels of chronic absence. Why is the framework for the conditions for learning even more important now?

David: The stakes for children and families and communities are greater than ever. On the one hand, there are all sorts of things that are going on in young people’s lives that really necessitate them developing and becoming people who have the skills that can help them survive in a world that is going to be in consistent disruption even if Covid becomes endemic.

But at the same time they’ve also had experiences during this last year, sometimes good and sometimes not, that do not ready them to go back into a situation where they don’t feel physically safe, where they don’t feel mentally safe, where they’re not engaged and where they are making a choice, not consciously, but unconsciously, about what is worth investing in. A decade ago, if we were in schools, public and private, and you looked around, you would see students who were really actively engaged in school, and there were other students who did what they could to avoid being in school, just like I did! But now, if there isn’t a reason to be there, then it is even harder to be there.

Hedy: Why was that important to add well-being to the condition of adult and student social and emotional competence?

David: As I learn more, I understand how the ability to express in oneself and support others’ social and emotional cognitive attributes and capacities is affected by how we are in terms of our will well-being. Well-being has a subjective element and it also has a biological element. We now know, with good science behind it, that there always will be an inextricable link between the mind and the body. And at the same time there is that inextricable link between people, because my well-being contributes to my ability to support your well-being, and my ill being leads me to do things that may contribute to your ill being.

Important work by Mark Greenberg and Patricia Jennings* has really shown the importance of adult well-being. And it is both adult well-being and young people well-being. [It is easier for a teacher] to not be stressed in her or his response to a student when the teacher is less stressed. That stress can be from worrying about something they have to do in school, or it can be the stress that people have in other parts of their lives. This all happened before Covid, but it is even more significant now.

* Jennings, P. A., Minnici, A., & Yoder, N. (2019). Creating the working conditions to enhance teacher social and emotional well-being. In D. Osher, M. Mayer, R. Jagers, K. Kendziora, & L. Wood (Eds). Keeping Students Safe and Helping them Thrive: A Collaborative Handbook on School Safety, Mental Health, and Wellness (pp. 210-239). Westport, CT: Praeger.