This is the fifth in our blog series highlighting attendance-related issues that are emerging as states begin to implement the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). In this post, we focus on the need for districts and schools to address chronic absence with positive, proactive, and problem-solving strategies, not punitive ones.

Read the previous blogs in our series, ESSA Implementation: Keeping Students with Disabilities In School, A Sea Change in Defining and Responding to Poor Attendance, High Quality Attendance Data is More Important Than Ever, and Making the Most of Attendance Indicators.

Now that all states are required to report chronic absence data, and that 72 percent have chosen it as an ESSA accountability indicator, improving chronic absence is certain to be higher on schools’ agendas in the coming year.** Focusing on chronically absent students, or those who are missing 10 percent or more of school days, is a tremendous opportunity to improve education outcomes. At the same time, this increased accountability creates an imperative for LEAs and schools to examine their approach to student absences.

Why? We all know the definition of insanity: responding to poor outcomes by doing more of what we have done in the past and hoping for a different result.

To date, our efforts to reduce absenteeism have been strongly flavored by punishment and blame. Throughout the U.S., lawmakers have enacted compulsory attendance laws and charged the courts with the ultimate responsibility to enforce them. The courts, in response, instituted civil penalties for truant students and their parents, such as tickets and fines. Many instituted criminal penalties, such as jailing parents, when a student’s unexcused absences rose above a certain level. For their part, districts and schools also implemented policies to punish truants; some do not accept make-up work from truant students, others bar them from extra-curricular activities, dis-enroll them from school or suspend them for excessive absences. Even when students’ absences are excused, the lack of support for them to catch up can feel like punishment.

Despite the fact that punitive practices are widespread, a growing number of researchers have found that they are not particularly effective. Studies on the effect of interventions for all types and levels of absences have found that efforts to address root causes have increased attendance, while punitive practices have not. Simply put, effective approaches are those that treat student absenteeism as a problem to be solved, not a behavior to be punished.

What Can Educators Do?

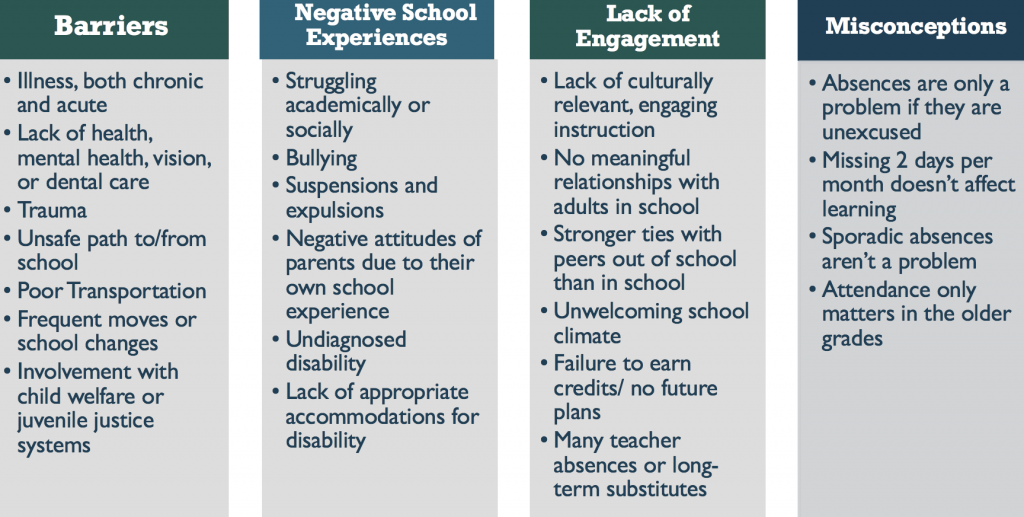

To change the current thinking and practice related to student absence, states, districts and schools must begin by helping educators to understand the causes of their students’ absences and, next, by helping them address absences with proactive, positive, problem-solving strategies. The chart (below), drawn from research and our experience working in states and districts nationwide, includes the most common causes of student absence.

Factors that Contribute to Chronic Absence

In this chart, the reasons for chronic absence are not sorted into the typical excused or unexcused categories, but rather into categories that reflect the drivers of absences. For example, absences due to barriers, those listed in the first column, are those due to experiences and conditions that arise from factors outside of the school and outside of the control of families and students. Nonetheless, schools and districts have power, connections and resources to address virtually all of these.

The second and third columns describe the negative and non-engaging school experiences that can often lead to chronic absence. Notice that the absences in these two columns are considered unexcused in many U.S. schools, and yet most, if not all, involve changes to the school environment, teaching, curriculum or program that can only be addressed by the school.

The fourth column involves misconceptions about the importance of attendance; to solve these, schools must deliver clear and consistent messages to educators, families and students and the community as a whole.

With a broader understanding of why absences occur, the next step in a process to address absences is for district and school staff to scrutinize their chronic absence data. Doing so means that student absences do not slip by unnoticed, but rather, they are addressed before they accumulate and cause serious learning deficits. Under the older, truancy-based approach, educators would not take note of absences -much less intervene- until students had missed a significant amount of instructional time.

In addition to promoting early action, the analysis of chronic absence data often challenges assumptions about attendance and reveals unknown attendance patterns of individuals and groups of students. Such was the case in Little Rock, Arkansas, where educators and administrators had long believed that children who lived far away from school were often absent, despite the fact that they were provided bus transportation. As a result, there was little confidence that their attendance could be improved.

An analysis of the district’s data, however, revealed that children who lived far enough away to qualify for busing were not poor attenders. Nor were students who lived nearby. It was the students who lived too near to be eligible for bus transportation, but too far to walk easily and safely who had poor attendance. With this new understanding, the school had several options; for example, it could approach the district to revisit bus policies, arrange for walking school buses, and/or reach out to local police and community partners to monitor routes to school. The important point is that the data analysis changed both educators’ beliefs about the reasons behind student absences and their understanding of the needed interventions.

This example is not unique. Consider absences due to illness – an excused absence that educators often believe is beyond their control. Regular analyses of schools’ chronic absence data can help identify those students who are missing school frequently due to unmanaged chronic physical or mental illnesses.

School staff can then connect families and students to nurses, mental health services and other community health care resources to improve their treatment and increase attendance. While these cases may require outside partners, it is school staff that have access to attendance data and, thus, the process of analysis must start with them.

Often, the data will raise questions that will require further investigation. Educators play a key role in sleuthing out the answers to unexplained absences, because they are the professionals who have the most contact with students, they are likely best able to develop the relationships with students and their families that are the key to understanding absences. Educators are also best positioned to notice absences, to begin problem solving and, to bring in additional supports and resources when needed.

In summary, schools must use a problem-solving approach to identify the causes of and solutions to absences, regardless of whether the absence is considered excused or unexcused. This framework will point the way to approaches and solutions that make sense to students and families and make it easier for students to be in school regularly. Doing so will likely require a shift in educators’ thinking about their role in addressing absences, especially those due to truancy, student discipline and illness. Nonetheless, educators must resolve to tackle these issues if they are to reduce chronic absence levels significantly and make schools accessible and welcoming to all.

Jane Sundius is a Senior Fellow with Attendance Works

Read the previous blogs in our series, ESSA Implementation: Keeping Students with Disabilities In School, A Sea Change in Defining and Responding to Poor Attendance, High Quality Attendance Data is More Important Than Ever, and Making the Most of Attendance Indicators.

**There is not yet a consensus about how to define chronic absence; however, most researchers and EdFacts are defining it as the percentage of students who have missed 10 percent or more of their days on roll in that school year.