California state leaders—including lawmakers and education, human services, law enforcement and judicial chiefs–gathered in Sacramento last Thursday to recognize Attendance Awareness Month and launch an interagency effort to combat chronic absence. A report released Friday underscored the extent of the problem in the nation’s largest state.

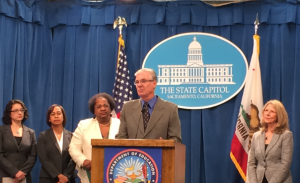

In Sacramento, State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tom Torlakson, Secretary of Health and Human Services Diana S. Dooley, Assemblymember Shirley Weber, Superior Court Judge Stacy Boulware Eurie and Special Assistant Attorney General Jill E. Habig each committed to address chronic absenteeism in their own arena. Read more here and watch it live here.

“All of us have a part in preparing California’s children for brighter futures,” Torlakson said. “Through local and state collaboration, we can improve the overall health, safety and wellbeing of our children by promoting public awareness and reforms that improve attendance.”

They also called on the state to do a better job collecting and reporting on all aspects of attendance. California is one of a handful of states that does not collect attendance data in it student data system.

On Friday, California Attorney General Kamala D. Harris released a report documenting the levels truancy and chronic absence in elementary schools, noting high rates among African-American students, foster children and children who live in poverty. The report, In School On Track 2014, updates an analysis done last year exploring attendance problems statewide.

“This is a solvable problem,” Harris wrote in her report’s executive summary. “If local agencies have the information necessary to illuminate these patterns, they can direct resources to the students and families that need them the most.”

The overall numbers in Harris’s report showed attendance remains a problem across the state: About 250,000 elementary school students were chronically absent in the 2013-14 school year, meaning they missed at least 10 percent of the school year, or 18 or more days. Even more students were truant, meaning they missed 3 or more days without an excuse. The analysis showed:

- African-American students had higher rates of chronic absence than any other group. Nearly one in five African-American elementary students, or more than 33,000 students, missed 10 of the school year. That’s a rate two and a half times higher than that for white students.

- Suspensions accounted for an estimated 113,000 days missed in kindergarten through sixth grade. Again, African-American students were suspended at disproportionately high rates: They missed twice as many days to suspensions per student as white students did. So did Native-American youngsters. For special education students, the rate was three times higher than other students.

- Low-income students continue to struggle with attendance, with about one in 10 suffering from chronic absence. About 15 percent of homeless children were chronically absent.

- Foster children had high rates of absenteeism with 10 percent missing too much school. The rates could be even higher, the report states, since foster children frequently move from school to school. These and other migrant or mobile students could be tracked more easily if the state collected and reported data from all districts.

We’re pleased to see the state leaders keeping the issue of attendance in the public discourse. Equally important, the leaders and the report shine a spotlight not just on truancy but also on chronic absence, a metric that includes both excused and unexcused absences.

When schools focus only on truancy, they can miss the fact that many young children are missing too much school in excused absences, as well. Young children can miss a lot of school due to illness, lack of transportation or simply because families don’t recognize how easily absences, even in the early grades, can jeopardize learning.

Just two absences a month can cause a child to fall off track. Whatever the reason, schools need to find out who these students are and work with families, in ways that are supportive not punitive, to get them back to class.

We were also pleased that the leaders and the report call for better attention to attendance data. We can’t target resources effectively if we don’t know which students, schools and communities have a problem with poor attendance.

California is a mixed bag when it comes to data collection. On one hand, it is one of just a few states that doesn’t track student attendance data in the state-wide database it maintains. That means state officials can’t track attendance trends among districts, schools or grade. And they can’t follow students who move from one district to another.

At the same time, California is asking its 1,100-plus school districts to track chronic absence data as part of a new Local Control Funding Formula. In the first year of implementation, barely one in five districts provided the information.

We hope this interagency effort will spur more districts to track this important data, because you can’t take action to improve attendance until you know there’s a problem in the first place.