The recent shift in federal education policy prompted by the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) has helped raise the stakes for schools around student absences. Under ESSA, at least 37 states are now looking at school-level chronic absence rates as their non-academic indicator in their ESSA plans. The implications of this are important. Previous policies assumed that parents were primarily responsible for attendance and answerable to absences. Now in many states, state policy indicates that absenteeism is an issue that schools have to address.

What, then, are schools to do in order to move the needle on student attendance? As researchers work toward understanding the impact of different interventions and practices, on-the-ground experiences in schools highlight the pervasive use of incentives from pre-kindergarten to grade 12. Schools have employed a wide range of incentives to improve attendance, with varied levels of success, according to senior researchers Rekha Balu at MDRC and Stacy Ehrlich at NORC at the University of Chicago.

In their article published February 2018 in JASPER, Making Sense out of Incentives: A Framework for Considering the Design, Use, and Implementation of Incentives to Improve Attendance, Balu and Ehrlich provide a framework to help school staff think about how—and when—to use incentives to improve student attendance. A number of other earlier research studies show the negative impact chronic absence has on student academic achievement.

Many schools are using incentives to try to improve student attendance. Incentives can be financial, social, informational, or some other type of inducement intended to change a behavior (in this case, reduce absences). Some schools use incentives for recognition, such as hallway recognition boards or stars placed on the lockers of students with high attendance. Some schools use an after-school activity, such as a dance program, to incentivize students to come to school.

In other cases, such as in some schools in Tennessee and Missouri, more costly incentives have been used, including cash rewards, cars, or tickets to sports games. These align well with universal, Multi-Tier System of Supports tier 1 practices, as they are aimed at all students within a school.

Sometimes school attendance is incentivized by outside or government agencies. For example, the Family Rewards program implemented in the Mayor’s Office in New York City included 22 different incentives for parents and students including financial incentives for families whose children attended school at least 95 percent of scheduled days in a month. Other programs are structured as penalties, with money deducted from families’ accounts when attendance was not high enough.

Because the research indicates that the effectiveness of incentive programs is mixed, Balu and Ehrlich suggest that making sense of these mixed results requires us—and schools trying to implement attendance incentives—to step back and consider if incentives are an appropriate intervention, and then how to design incentives in ways that address the specific attendance barriers.

Educators should consider what the problem is the incentive was trying to solve, whether it was designed to match the nature of the problem , how each incentive is implemented, and if the incentive is designed to influence behavior of the person(s) who mostly likely made decisions about school attendance, Balu and Ehrlich write.

Framework for thinking about implementing incentives to improve student attendance

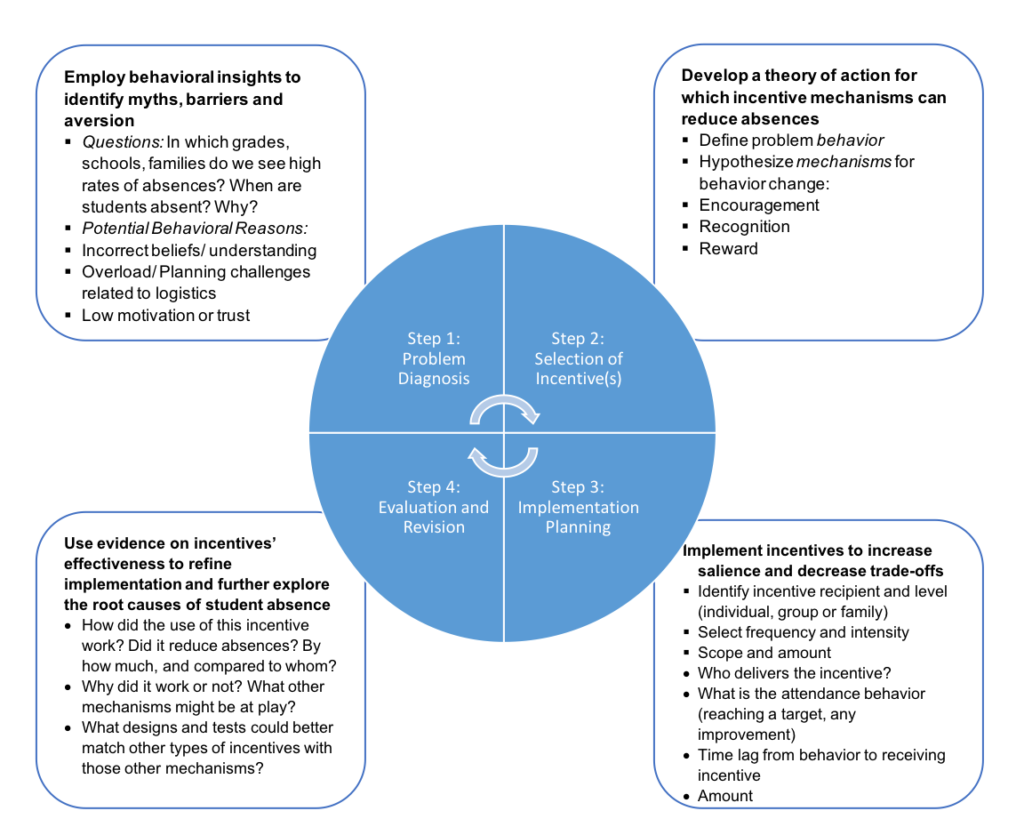

As schools work to figure out which interventions might best help them reduce student absences, Balu and Ehrlich find that it is most important for educators to focus on the design choices around using incentives and consider whether they are likely to produce the desired effect. The following four sets of questions (also in the graphic below) can guide the use of incentives to improve attendance:

-

- Problem diagnosis: What are the specific attendance problems/causes that need to be solved?

- Selection of incentive(s): What type of incentive should be implemented in order to address the identified problem and change behavior?

- Implementation planning: How can the incentive be implemented in ways that increase its salience and decrease tradeoffs?

- Evaluation and revision: What do evaluation results of incentive-based approaches indicate about effectiveness and how to improve subsequent implementation?

While answering the questions raised in the framework above, schools can consider the following three criteria :

- Intensity – ranging from very low-intensity approaches such as public recognition of students with strong or improving attendance, to very high-intensity approaches like cash transfers to students with attendance above a particular threshold.

- Recipient – ranging from incentives that target the behavior of individuals or groups of students, to those that target the behavior of teachers or other school staff members, to those that target the behavior of parents. Incentive-based approaches can also have multiple targets at once.

- Behavior – ranging from one-time actions to ongoing attendance behaviors, and ranging from low or high-stakes consequences, depending on the amount, timing and structure as either a reward or sanction.

School attendance is one of the most consistent predictors of student’s academic success—from pre-kindergarten through high school. Research shows us that students with better school attendance have better learning outcomes, including earning higher grades, failing fewer classes, and having higher test scores. Under ESSA, schools now have the opportunity to design programs that help students get to school every day. Incentives can be a part of a comprehensive, school-wide approach to reduce chronic absence. .

Rekha Balu is a senior research associate at MDRC and directs its Center for Applied Behavioral Science.

Stacy B. Ehrlich is a Senior Research Scientist in the Academic Research Centers at NORC at the University of Chicago.

Find the full study, Making Sense out of Incentives: A Framework for Considering the Design, Use, and Implementation of Incentives to Improve Attendance, published in JESPAR, (the Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk).