Washington, D.C., reduced its chronic absences rate in pre-kindergarten by 13 percent and increased by 15 percent the proportion of students with satisfactory attendance using a set of interventions anchored by more contact with families, according to a new report from the Urban Institute.

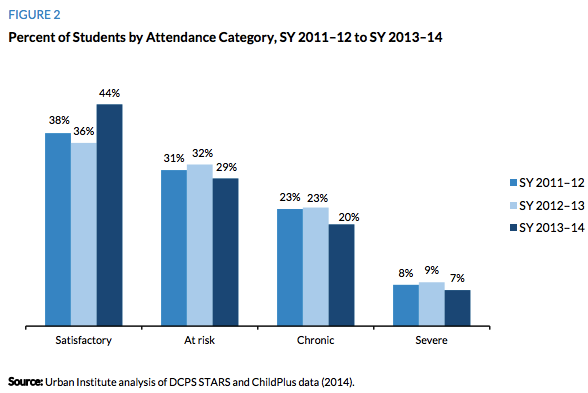

The report reviews three years of attendance data in the city’s universal pre-K program, which serves about 5,000 3- and 4-year-old students. The report shows that D.C., like many large cities, has an attendance problem in the early years: 20 percent of students missed 10 percent or more of the 2013-14 school year and another 7 percent missed 20 percent or more sf school days; that’s a total chronic absence rate of 27 percent. That compares to 31 percent two years earlier. At the same time, the percentage of students missing less than 5 percent of the school year rose from 38 to 44 percent.

So what did D.C. do?

The first step was to change its policy for calling pre-K families about absences. Rather than wait until a student had missed three days in a row, family service teams now call parents after the student misses three days any time during the school year. The interventions can also take the form of home visits or meetings with the teacher or principal.

The change in policy triggered taking supportive action with 30 percent of the students, compared to 7 percent two years earlier. In about 6 percent of cases, the school teams called in case management specialists to deal with more complex problems. That’s up from 2 percent two years earlier. According to the report:

This additional investment in family engagement has likely contributed to the increase in attendance. Identifying the unique role that this policy change has had on attendance is challenging, however, because other attendance initiatives across schools and within specific schools were occurring simultaneously.

In some ways, D.C. is unique. The city offers universal pre-K to all 3- and 4-year-olds through its schools. It has a hybrid model that braids federal Head Start dollars with local school funding, meaning that all students have access to family support services. In other ways, though, the challenges D.C. encounters in improving PreK are universal.

Preschool is a time when many students are first exposed to germs and spend many sick days at home. It’s also a time when parents don’t worry as much about taking a child out of class for a vacation or simply for family convenience. In most places, attendance in not mandatory in preschool.

At the same time, we know that preschool has enormous potential for helping children, especially those from low-income families, develop the academic and social skills they need to succeed. And recent research from Baltimore and Chicago shows that absenteeism in this earliest grade correlates with weaker skills development and worse attendance in later grades. DC’s approach, contacting and working with parents rather than penalizing them, seems a promising model.

“We are trying to get the message out that pre-K is not child care,” Deborah Paratore, director of Head Start program operations for D.C. Public Schools, told The Washington Post. “It’s a place where habits are formed, where children are going to school.”

The Urban Institute researchers also examined some trends in pre-K attendance:

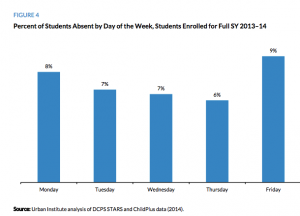

- Students are mostly likely to miss school on Mondays and Fridays. Absenteeism is also high on the days before holidays, half days and the days before or after snowfall.

- Chronic absence rates were highest among African-American students pre-K students, students whose parents speak English at home, students who were enrolled in TANF, and students who were homeless had much worse attendance than other students.

- Students are more likely to be absent in January and June.

A companion report explores the research and causes for absenteeism in the early years.